“What God allows in his Providence often seems to contradict his purpose.”

Getting that first Benji movie made was like careening through a mine field of slammed doors, unplanned disasters, catastrophic mistakes, and a noticeable vacuum of money, knowledge and experience.

I was convinced that God did not want this movie made. But it turns out he absolutely did. I just wasn’t ready! He had work to do. I had what Lee Domingue calls “a God-sized dream, which is what you have whenever it seems impossible, unreasonable, and too expensive, but you have a passion for it nonetheless. A passion planted by God.”

So it’s up to him to make you better, stronger. Many times I thought this is the end of life as I know it, but it all had to happen exactly as God planned it or neither Benji nor The Soul of a Horse would exist today. All of those adversities and obstacles were there to season me, to build my competence, my knowledge base, and to test my passion. For passion is what kept me from ever giving up and gave me the drive to find ways around those impossible obstacles. God was literally molding me with experiences that would provide the wisdom and tenacity to ultimately make it all happen against a great number of apparent odds.

The memoir below begins on my second day ever on the set of a real movie. The first time was back in college. I was an extra. This time I had written the screenplay and was producing and directing the film.

No one on the entire (very tiny) Dallas, Texas production crew had ever done a real movie before. Only the dog trainers were veteran movie makers. The rest of us had done our share of television commercials, industrial films, and maybe a short documentary or two, but there was no experience on a real movie anywhere in the group.

These were exciting times. These things actually happened. And those of us involved can say we changed the world, if only just a little. – Joe

Benji Begins Against All Odds

(Excepted from Joe’s book God Only Knows)

A single Indian Paintbrush shuddered in the first warm, breathless shimmer of morning, shedding the gray of night from its orange and gold tresses. It was a lonely remnant from the swarm of wildflowers that had danced here a few short weeks ago. Crystal droplets of dew began to sparkle on the tall grasses around the old house as dawn crept over the horizon behind me. The still morning air was moist, and layered with the fresh, sweet smells of country summer.

The seat of my pants was soaked. I had been sitting there on the damp ground for almost an hour watching the shadowy pieces come together for the initial scene of our first sit-in-a-theater-and-laugh-and-cry-as-you-eat-popcorn kind of movie. There would never be another morning quite like this one, and, for once, I had planned ahead to savor it. My homework was done. Each of the 443 shots in the script had been plotted, most of them diagrammed, casting was finished, the crew hired, locations selected, props and set dressings were approved, the arbor behind the house that Benji would climb to reach the broken window on the second floor had been constructed and aged and looked for the world like it had been part of the house for half a century; the opening shot had been described to all, and I had had nothing to do for the past hour but sit, and absorb, and reflect. And say a prayer. I was drifting in and out of the present, from the clanging of metal dolly track and the questions of the crew, back to a certain neighborhood theater where I had first shared Mr. Disney’s dreams. At long, long last it was happening. I was finally getting my chance to change places with the dream makers, to leave my seat in the theater and become the one reaching out to move, and entertain. To stir in others those wonderful feelings others had stirred in me. And I was anxious to get at it. I had been given a unique opportunity for a first picture. I was director, producer, writer, and president of the production company. No one could ruin it but me, at least, not without my permission.

A light breeze rippled the tall grasses around the gray mansion. The Indian Paintbrush danced a bit and then, again, grew still. I knew how it must feel, out there by itself. This was going to be a lonely vigil. The risk and responsibility were all mine and the weight of it scared me a little, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. This was my time! I had worked and waited forever, it seemed, for this moment, and I had promised myself that I would not allow the intimidation, confusion and frustration that I knew would be forthcoming to intercept or interfere with whatever I believed was right. The entire future was at stake, but I felt God and I were up to the task. Was I beginning to trust? Just a little? I think so. The lessons of a jigsaw puzzle, pieced together in a dismal hotel room in Dayton, Ohio, so many years before had never let me down. One piece at a time. One step at a time. No hasty decisions. No short cuts. Deal with each problem as it comes up, give it full attention, solve it, then move on. I felt like I was in the Notre Dame locker room listening to The Gipper. Whatever it takes, I thought.

“The other way, Tony!” I screeched above the clatter of equipment coming off the van. I was also the official yard guard, protecting the tall grasses that would be in the first shot from being trampled by a stray crew member looking for a shortcut. Tony had been lugging sections of steel dolly track into place for almost an hour.

“If I had known you wanted to dolly all the way to Waco, I would’ve called the Southern Pacific,” Tony grumbled. “Their track’s already in place.”

I hoped he was grinning. In the wisps of early morning light, I couldn’t tell for sure.

“You better hold it down out there if you want this dog to stay asleep!” It was the soon to be familiar bark of Frank Inn, dog trainer extraordinaire. Higgins, the dog playing Benji, was napping inside the old house. He had rehearsed the afternoon before and wouldn’t be awakened until the last minute because the shot called for natural sniffs, stretches and yawns, like he had just risen to greet the morning.

The search for Benji had begun back in April. The money for the picture was no sooner in the bank than I was on a plane headed west with several copies of the treatment‑cum‑revision-notes tucked under my arm. I spent a full week interviewing virtually every dog and dog trainer Hollywood had to offer and, by the end of the fourth day, things were looking awfully bleak.

Efforts to convince those weathered old trainers that Benji might be the toughest job they had ever encountered only evoked polite chuckles. A few expressed genuine sympathy when they discovered I was from Dallas and had never directed a motion picture before. I would explain the Benji concept, about it being from a dog’s point-of-view; about the dog acting, and how his ability to show emotion would have to carry the movie; and I would tell the story, just like I had told it to every one of our prospective investors, only where some of Dallas’ richest eyes would begin to moisten, these crunchy old trainers would merely wrinkle their brows and leap, with no emotion whatsoever, straight to the next “dog stunt.”

“Where’s the camera going to be when he does that? How many cuts in that scene? Strike that one, it can’t be done. I think you’d better build a phony foot for that.”

“Never mind all that right now,” I would plead. “Just listen to the story and try to get a feel for what we’re trying to do.”

“Feeling is your job, son. Dog tricks are mine.”

“That’s just the point,” I would say. “This is not a picture of tricks. It’s a picture of emotion.”

Nothing. Zero. I was speaking Greek.

I would ask to see their best dogs go through some paces. Then, I would attempt to duplicate a few difficult situations that might occur in the picture to see how the trainer would handle them. I suppose, in a roundabout way, I was trying to scare off anyone whose inner fires hadn’t been lit by the challenge. And it was working. I’ve never encountered such a negative bunch of people in my life. I would, later, when it was time to talk to distributors, but for now, these guys had a firm grasp on the trophy.

One absolute necessity was that, on occasions, the dog playing Benji would need to be trained into a specific action, then turned loose by the trainer, to do the action, more or less, on his own. That is, the trainer might be asked to back away so the dog wouldn’t constantly be looking at him. If, for example, we wanted Benji to trot down a path, pausing here and there to sniff, naturally, doggie‑like, we wouldn’t want him popping looks up at the trainer every few seconds with one of those Am I doing good? expressions.

An uncontrolled, duck‑like screech was usually the response to this. It showed, I was told, how very little I knew about making movies!

“If I turn my dog loose in the middle of a movie set,” said one, “with hundreds of people, and noise, and distractions, you’ll never get a shot and I’ll lose a dog!!”

Army dogs work in the midst of raging battle. Police dogs work in riot conditions. It seemed logical to me that a dog could be trained to trot down a country path without looking up at his trainer. I sensed, however, that this was not the particular trainer with whom to debate the issue.

“I’ll tell you how you can bring this thing off,” proclaimed another. “You film the dog chewing on food, and then dub in a voice, you know, like he was talking! It works great! Real Cute.”

I was striking out at every turn. And it wasn’t just the trainers. Many of the dogs I saw displayed personality traits that would never work for Benji. Dogs, like people, have vastly differing personalities. They can be arrogant, aloof, near cat-like at one extreme, and meek, submissive and dependent at the other. The latter group is probably the easier to train, but the result, enhanced, possibly, by the trainer’s methods, is a dog whose pleading, compliant expression is a constant reminder of how desperately he wants to please his master. His ears lie prostrate against his head, his tail wags feverishly, and his eyes are usually saying Oh God, please let me do good this time so I’ll get a pat on the head. To ask this type of personality to project character traits like independence and self‑reliance from a huge motion picture screen would be pointless. And the flow of looks from dog to trainer would continually interrupt any hopes for a believable character that could generate a true, emotional rapport with the audience.

Cute, sweet, monochromatic dogs and parochial, dogmatic trainers were keeping me up every night pacing the hotel room floor. I was beginning to panic. Every one I met with was saying the same thing, that what I was trying to do was simply impossible. Couldn’t be done. On the afternoon of the fourth day I drove over to Universal Studios to meet with the next‑to‑last name on my list. A young bird trainer named Ray Berwick. He had trained the flocks in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds and The Birdman of Alcatraz, and the cat in Eye of the Cat. Dogs, suffice to say, were not his specialty. But he was my first real glimmer of hope. He seemed to truly understand what I was trying to accomplish. He was excited about the concept, and the challenge. But he didn’t have a dog. Or, rather, he didn’t have one he felt was up to the task. His only dog was too young, and not fully trained. I asked to see the dog anyway. This man’s attitude was too wonderful to lose.

He was right, of course. His dog was a toddler, a mere puppy that would eventually grow up to play the title role on the NBC television series Here’s Boomer, but for now, for Benji, he wasn’t the right choice.

“What about other dogs?” I begged. “Couldn’t you find one, grow one, build one from scratch?”

Thankfully, he had the integrity to say that he couldn’t. He asked if I had seen Frank Inn and Higgins. My appointment was for the next morning. Frank was the last name on my list. If I drew another blank, I really didn’t know which way I would turn. I spent another sleepless night, much of it asking God if this is where I was supposed to be. Had I missed a turn somewhere? An open door that I didn’t see? Was He still at the helm or had I managed to miss the ship altogether?

The next morning I told the Benji story to a huge, balloon of a man, who sat across from me without saying a word for the longest time. He must’ve weighed at least three-hundred pounds, maybe more. I had no way of knowing. I had never been that close to anyone that large before. His eyes twinkled as he gazed off into space, twisting and twirling on a thick, walrus mustache with waxed, looping, curls on the ends.

He likes it, I thought. It’s funny how you can sometimes tell. So why didn’t he say so? I wondered how many times God would allow me to completely lose confidence – aka trust – before laying the good stuff on me. I’m glad He never told me the answer. It would’ve been dreadfully discouraging.

Across the table, a white sea-captain’s hat was trying unsuccessfully to corral a bushy, salt-flecked thatch of hair. I would learn that the hat never came off except at bedtime and then it hung only two feet away on the bedpost. I tried to picture this man with a beard. He’d be every kid’s image of jolly ol’ St. Nick. Despite his weight and his age, he looked remarkably fit and healthy. I guessed he was around fifty. I was wrong. He was fifty-seven.

I learned quickly to allow plenty of time whenever I asked him a question because his answers were usually woven into a loom full of fascinating yarns and anecdotes. A simple query about his background had yielded an hour’s worth of incredible tales, all marvelously told. This man would be wonderful with the press, I thought.

Frank Inn had lead a full and charmed life, beginning his animal training career in the mid‑thirties after being pronounced dead at the morgue, the result of an automobile accident. Fortunately, a second opinion sent him to the hospital, and, ultimately, home in a wheelchair with the news that he might never walk again. He lived alone, two thousand miles from any family, so a friend gave him a dog to lift his spirits and keep him company. Frank saw the dog as an extra pair of hands and a working set of legs and he began to train his new friend to do things for him that he had trouble doing for himself. It was a classic case of something wonderful and magical emerging from something tragic. Sitting there in that wheelchair, Frank fell in love, and he developed an understanding, a rapport, and a compassionate ability to communicate with an animal that few trainers have the opportunity to discover when training purely for money with specific tricks and structured routines.

The experience lifted his spirits, and the physical followed. He was soon walking again; but not quite well enough to return to his job as a rodeo clown, so he took whatever he could get. Fortunately for all of us, it turned out to be a job sweeping the streets and sound stages on the MGM studio lot.

One day, he paused to watch trainer Henry East on the set of The Thin Man—the original, with Myrna Loy and William Powell. East was trying to get the dog Asta to do a particular routine. It wasn’t working so the crew finally broke for lunch. Frank slipped over to East and told him that he had a dog who could do the sequence. “Show me and I’ll put you to work,” East said. But Frank’s boss forbade it, promising that he’d be fired if he brought his dog on the lot. At lunchtime the next day, Frank instructed his dog to dig under the back lot fence and follow him at a safe distance to the stage where East was working.

“The dog is supposed to run up the stairs,” East explained, “jump in the bed, dive under the covers, scratch around a bit, then poke his head out and bark. All in one shot. No cuts.”

Frank borrowed a ball from East and went to work. He took his dog up the stairs and placed him on the bed. He showed him the ball, tossed it under the covers, and let the dog dive in after it. Then he repeated the process, this time placing the dog on the floor before turning him loose. Next, he took the dog halfway down the stairs before sending him after the ball, then, once more from the bottom of the stairs, each time showing him that the ball was on the bed under the covers before letting him go.

He picked up his dog and climbed the stairs one last time, but he only pretended to place the ball under the covers, actually hiding it in his pocket. He carried the dog to the bottom of the stairs and told East he was ready.

The dog raced up the stairs, jumped onto the bed, dived under the covers and scratched around feverishly looking for the ball. Frank called his name, the dog’s head poked out from under the covers, Frank showed him the ball and said “Here it is. Speak!”

The dog barked, and Frank had a new job.

Since that day, in one way or another, Frank Inn had touched virtually every famous animal whose face had appeared on a motion picture or television screen. He assisted with Daisy and the pups in the original Dagwood and Blondie pictures. He assisted with Rin Tin Tin, and was with Rudd Weatherwax and Lassie for thirteen years. He broke out on his own with Rhubarb the cat who starred in the movie of the same name. He trained the cats in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Bell, Book and Candle. He owned Cleo, the talking basset hound on the long‑running television series People’s Choice. He trained Arnold the Pig on Green Acres, Tramp on My Three Sons, all of Ellie Mae’s critters on The Beverly Hillbillies, and most of the cats and dogs seen in pet food commercials during the sixties and seventies.

Of the several hundred dogs Frank owned, the one I had come to see—the one Ray Berwick had mentioned—was apparently light years ahead of his peers. His name was Higgins and he was in retirement, more or less, after seven years of playing Dog on the hit television series Petticoat Junction. Higgins had learned to do something new every week, thirty‑six weeks a year, for the entire run of the series.

“And now,” Frank said, “he’s a little tired. He’s thirteen years old and getting a much deserved rest. I’m a little tired myself,” he added.

There it is, I thought. That’s the problem. That’s what Frank is mulling over as he twirls and twists on that magnificent mustache. Benji was going to be a long and difficult shoot at best. Were the challenge and the accomplishment really worth the labor for a trainer and his dog whose sights were already set on retirement? Was the picture even possible with this first‑time nobody from Texas? Could he really pull it off? Or was he all talk? And the bills. Would they get paid, or, like so many independent productions, would this one end up as a bankrupt disaster?

“I should discuss this with God,” he said.

“I just did,” I said. “He said do the picture.”

We shared a smile.

Frank hadn’t responded emotionally to the story like Ray Berwick had, but he had listened intently and I felt that he understood what I was after. I also felt, as he continued to toy with the ends of his mustache, that the excitement of the challenge was winning.

“You know,” he finally said, “what you’re trying to do has never been done before…”

A huge lump lodged in my throat. I hoped he wasn’t going to join those who proclaimed the whole thing an impossible mess. No, I thought, he might think it. He might even say it. But this man will never truly believe that anything is out of his reach. We had, it seemed to me, at least that much in common.

“I don’t know exactly how we’ll go about getting it done,” he said, “but if you really like me and my dog, we’ll surely give it everything we’ve got.”

I tried to contain myself. We hadn’t talked money yet. I should smile quietly and speak softly, be an exhibit of control.

“Fantastic!” I blurted, leaping into the air and pounding the table with joy! I couldn’t have asked for a better attitude!

Moments later, I was outside, snapping pictures as fast as the wind lever would crank, talking all the time to Frank. “Too curious,” I said. “A strong, alert look. More intent. Even more. Now happy. Now sad. Try angry… determined.”

The big, golden‑brown eyes in my view finder were incredible! Frank was scuffling around behind me generating some astounding looks on the face of this veteran floppy‑eared star with the big reputation. Finally, I couldn’t stand it any longer. I stopped clicking the shutter and turned back to see exactly what Frank was doing to achieve the looks I was photographing. At that moment, he was waving a huge, white, flapping chicken around with one hand, while the other held a wreathing, wriggling snake behind his back, thankfully made of rubber.

Higgins was fascinated with the chicken. His eyes were wide with anticipation, clearly wondering what was going to happen next. Then, when he saw the snake, he recoiled with a snap, ready to dodge a strike. He had obviously encountered a snake before.

Frank understood! What a wonderful feeling of relief after a week of mounting fear! And he seemed to be having a good time finding ways to cue the looks I was asking for. It was going to work after all. The concept, the picture, everything!

Higgins was not exactly the portrait of Benji I had painted in my mind—colored, I’m sure, by memories of Lady and the Tramp—but that portrait would simply have to change. This dog actually looked more like Lady than Tramp, but those marvelous, expressive eyes easily devoured any perceived shortcomings. I was already his subject. And his personality was perfect. He was independent, curious, and interested in the world around him. He never failed to respond to Frank’s instructions but, almost always, it was with casual nonchalance, as if to say I hear you and I’ll do what you ask, but it’s because we know and love and understand each other, not because I’m begging for a pat on the head. And don’t you forget it, Mister.

I rewound my fifth roll of film, put away the 35mm and pulled out the Polaroid. So casual and matter of fact was Higgins’ attitude that I would often catch myself thinking that he hadn’t heard a particular instruction from Frank. But he would always surprise me and respond exactly as requested.

I was in love! For the first time I was seeing the words I had written and told so many times actually coming to life before my eyes. This dog was Benji. This man could make it happen. We spent the rest of the morning wandering through Frank’s kennels looking for Benji’s girlfriend, Tiffany.

In just a few short hours, the dogs had been cast, the deals made, and once again the future looked rosy. That night, I would be flying home on the red‑eye, on top of the world, after a terrific day, and a delightful dinner with Green Acres’ co-star Tom Lester talking old times. Tom was a fraternity brother from Ole Miss. It was while waiting to meet Tom that things got a little strange. I’ve rarely talked about it, because even good friends start backing away and looking for the door. I was sitting alone at a table in the bar of the Hollywood Holiday Inn, browsing over the dozen or so Polaroids I had taken of Higgins, mentally beginning to write the script, visualizing that wonderful face in first one scene, then another, when somebody put a quarter in the jukebox and punched up the love theme from The Godfather. Its haunting, soulful melody melted through my emotions. I found myself drifting deep into Benji’s story to see him cast out of the doctor’s house, sent into the streets, lost and alone. His friends were in trouble, but he was helpless to make anyone understand. I felt his despair, his spirit crushed, as he moped from one familiar haunt to another, looking for an ally, but finding only empty streets and closed doors. The music on the jukebox swelled, the strains of its minor chords wrenching at my insides as the camera in my mind drifted up, high above the ground, leaving Benji a mere lonely speck in an otherwise empty and desolate frame.

Suddenly I realized that tears were dribbling down my cheeks, and the men at the next table had stopped talking and were staring at me, mouths agape. I quickly gathered up the pictures, dropped too much money on the table for the beer I hadn’t finished, and disappeared out the door. But in those few moments, an entire sequence of the movie was written, and the importance of the role music would play in the final product was engraved upon my emotions in a manner I wouldn’t soon forget.

The next morning, back in Dallas, Frank was already calling. He wanted pages of the script sent to him as they were written. And he wanted them written immediately! I think panic was setting in. He must have re‑read the treatment after I left and now he was desperate for specifics so he could get a head start on training.

But I couldn’t begin the script until we had our key location nailed down. The old house in McKinney had just been purchased by a metal sculptor from Dallas who planned to move in right away and begin restoration work, which would ruin it for our purposes; and there wasn’t another house like it anywhere in the area. It was perfect. Old, rundown, neglected, haunted-looking, two story—all haunted houses are two story—and, it was au naturelle. It fit our story needs exactly as it sat, which was important because we had no money to make a house over. If we couldn’t use this particular old house, then the entire location concept would probably have to change. I supposed back to center-city and the old, abandoned warehouse. In any case, I couldn’t start writing until I knew.

Wherever Benji was to live, we had to virtually own that location for the duration of the production schedule. There would be several weeks of shooting in and around it, and it would be our only cover set for weather—a set that could stand, ready to shoot at any time in case the rains came. And, of course, we needed it cheap.

After a few days of unabashed begging and pitiful crying, the sculptor finally, graciously agreed to postpone his move for a few months and rent us the entire house for the duration of the shoot. Normally I would never recommend to anyone that they let a film crew anywhere near their home, much less into it. No matter how much care is taken, when that many people wielding that much equipment descend upon small rooms and delicate furniture, something terrible is bound to happen. But, in this case, the house was in such bad shape—it had been vacant for quite some time—I felt that our plans might even enhance its worth.

The old house became our headquarters. Production offices, dressing rooms, an editing room and the like were assigned to rooms that wouldn’t be used for filming. I spent several days walking through the house, studying its every nook and cranny, absorbing its feel, and working with Harland—who would be Art Director on the film—designing the arbor out back that would allow Benji climbing access to the broken window on the second floor. We decided on a second floor entry to point up Benji’s ingenuity, to subtly begin the process of letting the audience know that Benji could solve simple problems. A restricted access would also enhance one of the chase scenes, and a second floor entry would allow Benji and the audience a dramatic overview of the happenings on the first floor.

With the logistics of the location all clearly in mind, I finally sat down at the kitchen table and started to write. I tried writing at the office, but the telephones and general chaos eliminated any possibility of a moment’s peace. At least at home, for a few hours a day, Joe III was in school and Brandon took naps.

Frank was calling daily, screaming bloody murder for script pages. But those first few didn’t come easily. I must’ve started fifty times. That first page seemed so important, and I wanted every word to be perfect. The only way I finally got to page two was to force myself to stop re‑reading page one.

I finally amassed three, maybe four pages and rushed them off to Frank, thankful that, at last, his phone calls would stop.

But they didn’t.

“I can’t train that dog to go to the bathroom on cue!” he bellowed over the phone. The scene was part of the opening title sequence. Benji would be trotting happily through town, doing doggie-like things and I thought it would help the audience get into the character and forget they were watching a dog acting if Benji were to pause along his route and lift his leg behind a tree—with only his head and shoulders poking out, just enough to tastefully convey what was happening.

“I suppose I could make him just stop behind a tree,” Frank said, “and it might look like he was going.”

“No,” I sighed, “It wouldn’t look natural. The shoulder wouldn’t roll, he wouldn’t scratch the ground like dogs do. And his expression would be different.”

“His expression???”

Frank thought I was nuts. But I’d rather not do it at all than do it wrong. So I wrote it out. Higgins must’ve stumbled onto Frank’s original draft, however, because when the scene was filmed, he trotted jauntily through the grass and—completely on his own—paused behind the perfect tree and performed the desired action exactly as it had been originally written! On the first take!

As the script progressed, every evening we sent copies of the day’s pages to Frank, and before long I was able to predict his calls. I began to schedule lunch accordingly, around two in the afternoon, any day after I had sent pages in which Benji did something a little out of the ordinary. Like when he opens the pudding cup for Tiffany. This was way back when pudding cups came in aluminum cans. With sealed “pull-off” aluminum lids. No easy task for a dog with no fingers.

“Can we take the lid off and just lay it back on top of the can,” Frank pleaded, “then shoot it from a low angle and let Higgins just pick it up.”

“No, Frank. We can’t get the lens lower than a pudding cup without cutting a hole in the floor. And if there’s no struggle when he pulls it open, it won’t look like he’s really pulling it open, and there goes the believability quotient.”

If there’s one thing Frank got sick of hearing about it was my believability quotients.

“It can’t be done,” he said. “How’s he going to hold it down and pull it up at the same time? It’s impossible!”

If there’s one thing I got sick of hearing about it was Frank’s impossibilities.

These little tiffs were a precursor of what was to come when we started shooting. Our screaming matches on the set became legendary, but I’ve never seen two people who fought each other so hard, understand each other any better, care for each other any more, and when it was all said and done, be able to sit next to one another in a theater shedding tears and asking each other how the hell we ever pulled it off.

Like all of the other impossible things he couldn’t do, Frank worked out the pudding cup beautifully. It wasn’t actually pulling the lid off that worried him, it was Higgins’ lack of hands and fingers to hold the can down as the lid was pulled up. A single paw holding the cup from the top would be unstable and would get in the way of the top coming off. Frank and Harland worked out the ultimate solution by bolting an insert sleeve to a board. The sleeve was just slightly smaller than the pudding cup, but a tight fit. The board was nailed to the floor and a hole cut in the carpet. Then, for each take, it was a simple matter to cut the bottom out of a fresh pudding cup and slide it over the sleeve, which, of course, was filled with pudding. The cup, then, was held solid. It couldn’t slip and slide. Benji could put a foot on it, grab the ring with his teeth and pull till his heart’s content and the cup itself would never move. Thus, I’ve always provided honest answers to those faithless who keep asking if Benji really pulled the top off that pudding cup all by himself. Happily, no one’s ever asked if he held it down all by himself.

“Time to tense up. We’ll have full sun in five minutes.”

It was Neil Roach, our production manager. The butterflies began their cycle in the pit of my stomach. This was it. The first shot.

I glanced around at the crew. Most of them, like me, were experiencing this for the first time, many in jobs they had never performed before. The only person on the set who had ever worked on a full‑length motion picture was Frank Inn.

Lighting can play an important emotional role in the final look and feel of a film. I learned this the hard way, screening dailies from my first commercial at Jamieson, that fateful night-shoot around the campfire. After excusing myself from the screening room to go throw up, I had decided that there was no logical reason for lighting to detract from a scene when it could—and should—be enhancing it, nourishing mood and amplifying dramatic impact. The logical place to start—except for the obvious exceptions—was to design lighting that looked undesigned, natural to the situation being filmed; real, unlit. To do otherwise was to put on obvious display that we were making a movie, thus risking the believability quotient.

That term again.

To fully understand believability quotients requires a willingness to separate believability from reality. To work solely within the audience’s level of belief in a particular story or movie, reality notwithstanding. Does the story and its execution so envelop you that, within its own context, if only for the moment, you can accept everything that happens? In Star Wars, did you believe in the power of The Force? Did you believe that Han Solo’s spaceship could shift into warp speed? Millions did, and loved it. But when Solo and Luke stumble upon the death star, would you have bought it if Luke had suddenly reached far beyond his established limitations and invoked the full power of The Force to save himself and his friends? Not likely. He hadn’t yet learned enough.

Did you sit on the edge of your seat in Jaws? Did you believe in the characters and their trauma without regard for the fact that Great White Sharks never get as far north as Martha’s Vineyard? I did! Absolutely! I was even the first one in the theater to scream when that grotesque head dropped down. But how would you have felt if Roy Scheider had suddenly produced a laser pistol to kill the shark? Or invoked the power of The Force?

Did you believe the birds singing in Cinderella? The animals talking in Jungle Book? The monster in Frankenstein? The loving relationship between Elliot and E.T., even though, to our knowledge, such creatures don’t exist?

There you have it. Given the context of the film, the characters and the story unfolding on the screen before you are able to capture your belief and hold it hostage until you are once again back out on the streets of reality. And anything that disrupts that belief, that raises questions about the validity of a scene or a character’s action, that slaps you in the face with a reminder that you’re merely watching a movie rather than experiencing a story, however fantastical, dilutes the believability quotient and, in turn, diminishes the overall effect of the film.

The first shot on our production schedule was also the first shot in the script. This was not a result of prudent production scheduling procedures, but rather because I found it symbolic and simply couldn’t resist. Normally, on the first day, simple shots are scheduled to get everyone off on the right foot, primed with accomplishment. Me, I wheel out the toughest, most complicated shot in the script, laden to the brim with variables and timing problems.

FADE IN:

1 EXT. OLD HOUSE ‑ DAY

ESTABLISHING SHOT of an old graying two‑story house, once an impressive mansion, but now up to its porches in weeds. Bushes and shrubs grown out of control for years seem to shroud the house in shadows. The glass in a pair of upstairs windows has been broken out; a shutter hangs ajar from its bottom hinge and even on this bright summer morning, the old house stirs an unsettling feeling. It’s the kind of place that causes local kids to cross to the other side of the street. We hear morning sounds (birds chirping, a rooster crowing, a dog barking off in the distance) and we begin to move slowly, diagonally, across the yard, toward the house, studying it more closely, finally picking out an upstairs window that opens onto a side porch and we zoom slowly to an extreme close‑up of a broken‑out pane in the window. At exactly that moment, Benji’s head pops into the window. He’s a mixed breed, un-groomed mutt of a dog but somehow still projects a lot of class. At our first sight of Benji, bright, happy theme music begins. Our hero sniffs the morning air, yawns, stretches and climbs out through the broken window pane.

The shot would start with the camera virtually in the street on a wide shot of the house, then it would dolly slowly in toward one side, eventually rounding a corner to find the second‑story window where Benji would appear. The zoom would begin, almost imperceptibly, tracking slowly toward a very tight shot of the single pane where the glass had been broken out. The dolly and the zoom would stop at precisely the same moment, exactly one beat ahead of Benji’s face popping through the broken pane, yawning and sniffing the morning air as if he had just awakened for the day. The precision was necessary because the downbeat for the opening music would punctuate that exact moment and thrust us happily off into our story. It was all one shot. No cuts. And it had to be filmed just as the sun crept over the horizon to capture the feel of early morning light.

There were a hundred places for things to go wrong. But none of them could be allowed to show. This was the opening shot of an unknown film about an unknown dog, made by a tiny, unknown company, with unknown filmmakers. We had to snatch the audience away from their daily muddle the moment the film began to roll. There could be no technical distractions. Also, my paranoia assured me that certain segments of the industry would be lying in wait for us, anxious for flaws and imperfections to expose our backwoods inexperience. I was determined they wouldn’t find any. Benji was going to look like the best of Hollywood, which meant rejecting the shot if the dolly wasn’t smooth, if the zoom didn’t begin just right, if the focus changes weren’t on the money, if the zoom and dolly didn’t end together just as Benji popped into the window, if the final composition wasn’t right, or if Benji’s attitude didn’t project that he had just awakened to greet a brand new morning.

Tony pushing the dolly, Jim, the focus‑puller, Don Reddy, our Director of Photography, on camera, Frank Inn outside the house, his wife Juanita Inn releasing Benji inside, and Benji himself all had to coordinate perfectly for everything to work. We had spent three hours rehearsing the afternoon before because to rehearse now, immediately prior to shooting, would take the fresh, morning edge off Benji’s attitude.

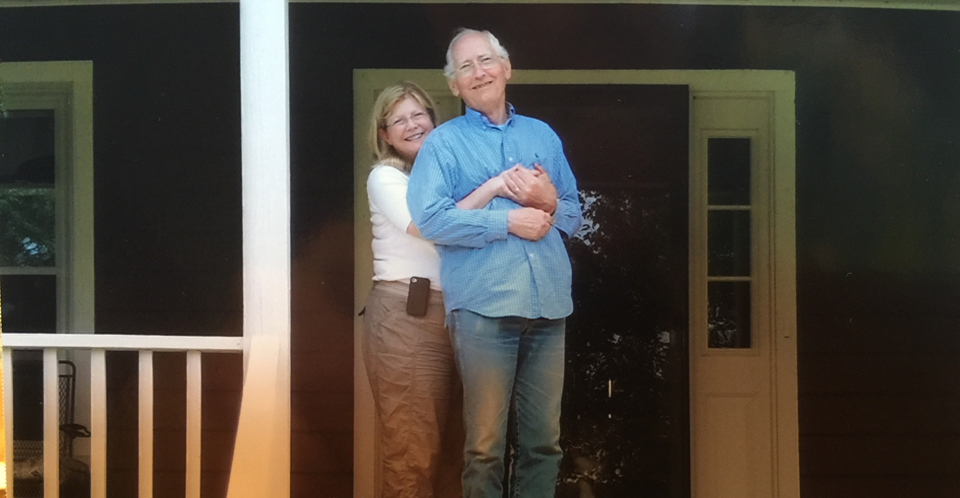

Carolyn slipped up next to me and entwined her fingers in mine. “Good luck,” she said.

“I wonder where it’ll all lead,” I said. “I wonder where we’ll be a year from now, ten years from now.”

She squeezed my hand and I felt her tremble. I sensed that she was once again torn between the wish for success and concern over the changes it might bring. But, outwardly, it didn’t show. She was working as hard as anyone on the set. She had signed on to do makeup, but weeks ago she had been handed hairdressing and wardrobe. She was also helping the script girl with continuity and Harland with props, and, in her spare time, she was magically handling the multitude of odd jobs I tossed at her when I felt I could trust no one else to do them. She was, in effect, the producer, but it was years later before I finally realized it and gave up to her the unencumbered responsibility, and the title.

Joey, now twelve and insisting that everyone call him Joe, or, at least, Joe III, worked the entire summer on the set, assisting Frank and Juanita with the dogs and helping the grips and electricians tote lights and equipment. It lead to a career. Primarily as a first assistant director of huge movies, but he has also written and directed a picture of his own entitled Abilene. Brandon, who would become one of Hollywood’s highest paid writers at a very young age, was at home with a baby sitter,

“If nothing else,” I said to Carolyn, “at least we’re starting out well prepared.”

Of course, I shouldn’t have said that. At least, not out loud. The opening shot was the first shot we filmed and, eleven weeks later, it was the last shot we filmed. In all, we photographed the opening scene of Benji eighty‑four times. It became a weekly event, something everyone could count on, like inflation.

On the very first take, the camera was perfect, the timings were right and Benji’s actions and attitude were exactly what I had hoped for. He looked for the world like he had just awakened for the day, because, in fact, he had. But the lighting on the house was wrong. The aging mansion faced east, bathing its old, graying visage in the direct rays of the early morning sun, shining deep orange through the haze of our metropolitan atmosphere. It looked like we had filmed at sunset! I wanted to kick myself. I should’ve known better. I was so sure everything had been thought out.

Too late, the solution was obvious. We’d have to shoot the scene back‑lit, in the afternoon when the sun was setting behind the house. This would overexpose the orange out of the sky and leave the house seemingly veiled in a softer, cooler, morning-type light. We set it up for a week later. Benji’s “portable” one‑ton air conditioner had to go back upstairs. The scaffolding outside the window had to be re‑erected for Frank, and the dolly track had to be re‑laid across the front yard. Needless to say, the crew was less than tickled. Nobody likes to do the same work a second time. A job finished should stay finished. To do it again is to halt progress and start going backwards. And, I suppose, it’s worse when the reason for this rearward motion is someone else’s mistake. The roar of the whispered grumblings rumbled across my senses trying to flatten the bulwarks I had erected. I dug the trenches deeper, repeating the admonitions I had preached to myself. No short cuts. Deal with each problem as it comes up. Give it full attention, solve it, then—and only then—move on.

This time the house looked terrific! But when Benji pulled himself into the window he looked like he had been hit by a truck. He had been slaving in the melting Texas summer heat for almost twelve hours and he was completely done in, tongue hanging out a foot.

The next week, we tried again, this time letting Higgins take a long nap in an air‑conditioned room before shooting. He was better, but, to him, it still wasn’t morning so there were no sniffs. By now we had decided to take the yawn in a close‑up right after the sniffs. But the sniffs had to be there. It had to feel that real. Editing can solve a lot of problems, but it can’t make a bored dog appear fresh and alert. Dogs love mornings like humans love Spring. Each one is filled with the anticipation of marvelous new discoveries. This is how I wanted the audience to see Benji for the first time, wrapped in his own environment, doing his own thing, not a trick dog doing stunts for a movie.

We had to have sniffs!

“He’s over the edge,” I heard Juanita say one afternoon as we prepared to shoot the opening shot for the fifth or sixth time. And by now, the crew was seriously considering mutiny. Others in the industry around Dallas who were not working the picture were hearing the tales and beginning to needle those who were.

“Camp obviously doesn’t have the vaguest idea what he’s doing,” they were saying. “The picture will never get finished.”

What they failed to understand is that whatever the level of truth that was attached to the first statement, it had no bearing on that of the second. But, the words didn’t set well with a crew who, for the most part, had deferred some of their wages for shares of the profits. Morale began to sink.

It would’ve been very easy to give up and simply make do with whatever we had. I dreaded facing the crew each time I wasn’t satisfied. Finally, one morning I gathered everyone into the living room of the old house and stumbled my way through a pep talk. The problem had become very personal, but also very important, I felt, to the outcome of the picture.

“I don’t believe that being good at something is predicated upon being an expert, or being perfect,” I stammered. “Or being above mistakes. What I do believe is that being good demands a willingness to recognize those mistakes and correct them. To look beyond the criticism of the moment to make decisions that are hopefully best for the project in the long run, when, for example, a year or so from now an audience is sitting in a theater daring us to entertain them.”

When we left the room we had lost almost an hour of shooting time but the dividends were readily apparent. The crew was back on the offensive and aggressive in their work, even with Scene RRRR1.

Whenever a scene is re‑shot, an R is placed before the scene number to distinguish it from the original. If it’s re‑shot twice, two R’s precede the scene number, and so on. By the time we were finished with Scene #1, the R’s were running off the slate. Each time there would be some new idea, but nothing seemed to work until the last week of production. We let Higgins sleep for almost six hours before the shot. We put six strips of bacon into an electric skillet, upwind, out of sight so Benji wouldn’t look at it, let it come to full sizzle, the aroma wafted along by a small electric fan to land right under his nose. When he popped his head through the window, he sniffed the air like it was a fresh new day.

“Cut and print!” I shrieked happily. It was the seventy-ninth time the scene had been filmed.

Two weeks into the shoot Don Reddy, our Director of Photography, quit. And I had to talk him out of it.

Record rainfall ‑‑ 9.38 inches, four times the July norm! ‑‑ buffeted and sank our schedule.

When it wasn’t raining, it was so hot we had to trade in Benji’s one‑ton air conditioner for a three‑ton unit to keep his tongue from dragging the ground. It was a standard home compressor, huge, heavy and not very portable, yet it had to follow him everywhere, gobbling up unscheduled time and money.

The actress we flew in to play the neighborhood lady with the cat persuaded—intimidated—me into letting her play the scene a bit tipsy. It wasn’t right. I knew it at the time. And the dailies confirmed it. Every night for a week I would go upstairs to the editing room and ask Leon to put the film up again, hoping each time that the scenes would look better. They never did. We had to throw the film away, fly in another actress and shoot the scenes again.

Which meant Frank had to fly the cats back into town to start their training over from scratch.

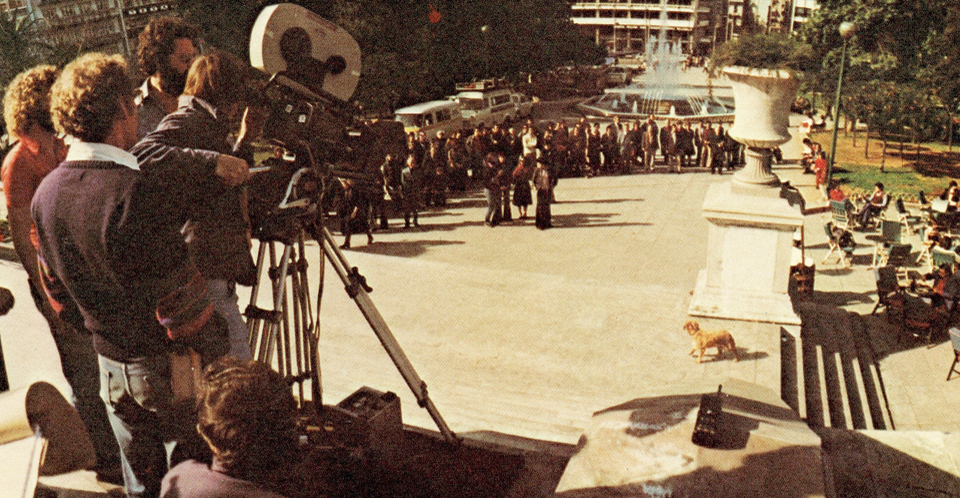

The Dallas Parks Department decided to spray the grasses of Samuels Park with a highly toxic insecticide, dangerous to dogs, on the very day they had given us permission to shoot the slow motion love montage.

The actor playing the kids’ father was commuting by car to Austin every night to star in a dinner theater production of The Rainmaker. He had promised, of course, that the play would have no effect on our schedule or his ability to perform in Benji. And, of course, he was late to the set most mornings, missed several calls completely and was generally incoherent when he showed up.

He fell asleep at the wheel one night on his way back to Dallas, hit a tree and wound up in the hospital.

Actors Christopher Connelly and Mark Slade had decided before arriving in McKinney that real movies couldn’t possibly be made this far from Hollywood. To them it was a joke, and their attitude was undermining the morale of the cast and the crew.

We discovered that Tiffany was typecast. A dumb blonde. Couldn’t act a lick.

Our second try at the scenes in Samuels Park found huge sprinklers exactly where we wanted to shoot. 9.38 inches of rain wasn’t enough for the Dallas Parks Department. The sprinklers could not be shut down for a day, nor could they be moved. We had to wait.

The hundreds of butterflies collected for the end of the love montage all died.

Twice.

My seven‑week schedule stretched to eleven and Ed Vanston, our chief investor, had to raise more money to cover the extra time, only to find, once the picture was edited, that it was too short. Still more money had to be raised, I had to write another ten minutes into the script, fly Higgins, Frank, Juanita, Patsy Garrett—the wonderful actress playing the housekeeper—and Terry Carter, the actor playing Benji’s policeman friend, back to Dallas, rehire the kids and the crew and shoot another full week, trying to match winter for Summer and avoid the Christmas decorations now hanging from every streetlamp and store window in McKinney.

Seven‑year‑old Cindy had lost two front teeth in the interim. And the trees that had shadowed the back porch during the Summer had lost all their leaves.

Higgins began the picture with a full, thick coat of hair, but by the hot Summer’s end, he had shed so much of it that the nub of his tail was actually showing. The change was barely noticeable as we progressed through the eleven weeks of shooting, but when scenes shot out of sequence, weeks apart, were cut together, our fat, fluffy, full‑coated dog, in the blinking of an eye, would lose all his hair, then miraculously get it all back again. Not unlike Cindy’s teeth.

But through all the mistakes, mishaps, detours and delays, the most important element of the picture was working. The point-of-view and the emotional heart of the story were leaping off the screen with more fidelity than I had hoped for. Even screening raw dailies, with scenes out of context, out of sequence, with slates, and crew noise, and Frank’s voice on the track, when Benji’s face filled the screen and those big brown eyes went to work, truly magical things were happening! Benji was acting!

“If this were MGM, they’d dig me a hole!”

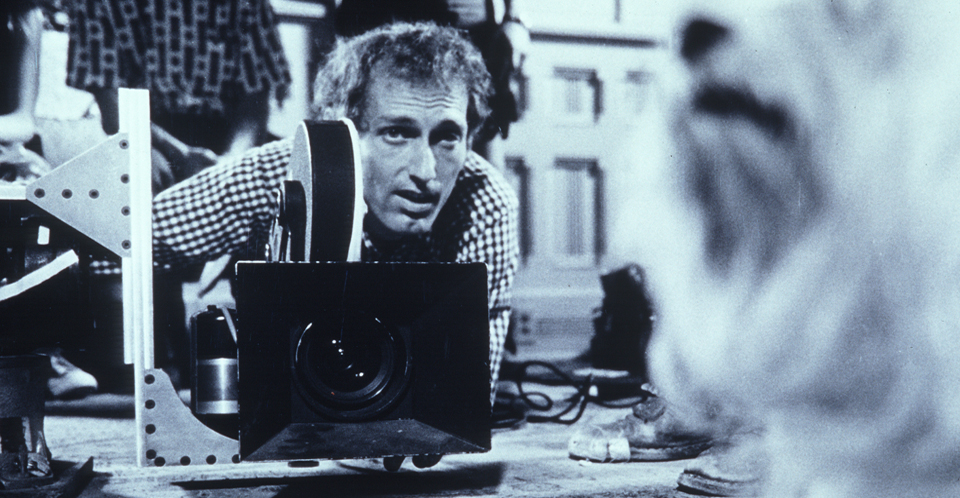

Frank was barking at no one in particular, but the line was to become familiar. He was lying on his 300‑pound belly, scrunched as close to the camera as possible and I was sprawled on top of him. Jim, the focus‑puller, was on his knees with his elbow jammed in the small of my back. Don Reddy was hunkered behind the eyepiece and Tony was wedged between the wall and the camera trying to place Benji’s eye light right next to the lens. We had discovered early on that without the pinpoint of reflected sparkle created by this tiny light, Benji’s eyes became dark, expressionless holes. It’s amazing how much difference it made, and invariably, for maximum effect, the light needed to be exactly where Frank had settled in.

“Put it where Benji will be looking,” Don would always say. It had to do with geometrical things, like angle of reflectance. But, of course, Benji, in close-up, would usually be looking at Frank and the ever‑wagging finger from which he took his instruction. So, we spent months trying to repeal the physical law against two solid objects occupying the same space.

“Watch your finger, Frank. You’re making shadows on the dog’s face.”

“I wouldn’t know. I can’t see the dog’s face!”

“Can you move over a bit?”

“How’s this?”

“No, his look’s too far off.”

“Try this.”

“Too low. Can’t you keep your hand behind the light?”

“If my dog can’t see it, he’s not going to do what Joe wants him to do! Move your damn light!”

“If the light’s not there, it won’t matter what he does!”

Normally, when tempers flare like this on a movie set, there’ll be a methodical build to a final insult, a screaming retort and one or more of the parties will stomp off, adult‑like, until he or she or they cool down. But there was nothing normal about our set. We were usually piled on the floor at Benji’s eye-level, shoe‑horned into some corner where nobody could move, much less stomp off, so there was little choice but to deal with the problem.

We spent the better part of three months like that, on our knees and bellies, stacked on top of each other, scrunched into impossible spaces attempting to look up at our fluffy hero. Placing the camera just slightly below an actor’s eye-level tends to make him appear stronger, more in control, more heroic. But there’s a hidden side effect. Even though Benji’s size is clearly defined by shots with people and other animals, whenever he makes personal appearances, there are always those who are astounded that he’s as small as he is. The low camera angles tend to create a larger-than-life feeling that outlasts the intellectual reality of, for example, seeing him easily cuddled in the arms of a pint-sized seven-year-old. It’s not a new phenomenon among short actors.

The word short, of course, is relative. Placing a camera below a human’s eye level, however short, creates no unusual problems. But Benji stands a mere thirteen inches off the floor. And much of the time he was lying down. New camera rigs and devices had to be designed virtually on a daily basis. How does a camera, for example, precede a dog at dog’s eye level running down a narrow sidewalk at thirty miles an hour?

Back when the script was in the typewriter, I tended to worry more about story than production problems, managing to overlook—or possibly choosing to ignore—the simple fact that a heavy motion picture camera usually works better when attached to something like a pan head and a tripod or camera dolly. The head allows the camera to be smoothly panned or tilted, but for the head to be stable, it has to be attached to something like a tripod. The shortest something known to the motion picture world prior to Benji was called a high hat, topping out about six inches off the ground. The pan head lifted the camera another eight inches, already above Benji’s eye‑level before adding the distance from the bottom of the camera to the lens.

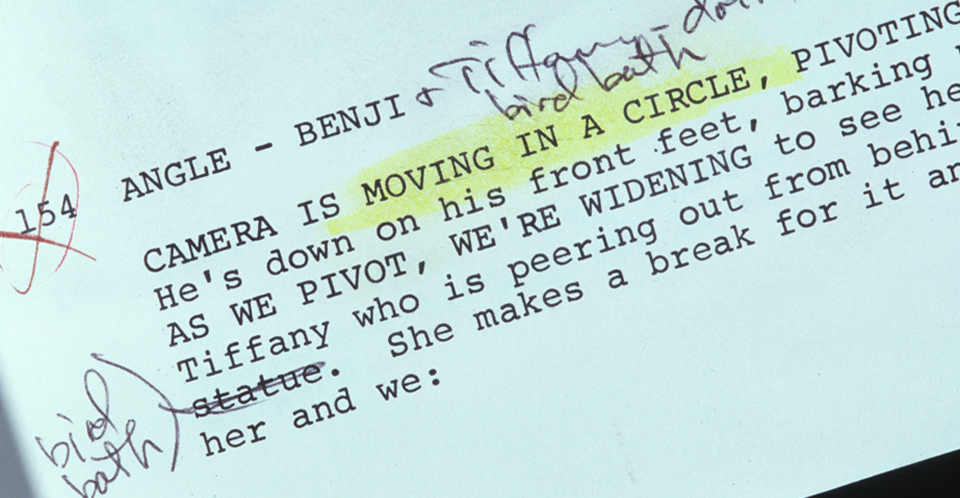

Jim and Tony came up with an entire arsenal of creative new gear, from simple plastic lazy susans bought at the dime store for $1.98 to complex welded rigs that hung off the sides of camera dollies, dangled from pickup trucks, dropped off the bases of various pan heads, and circled birdbaths like merry‑go‑rounds. I believe we even had the first skateboard in the world. But it transported a camera, not a teenager. The lens was simply never allowed to look down on Benji unless there was a special and specific reason for it to do so.

Bruised knees, sore backs, and grimy clothes from lying in the dust and dirt were the order of the summer. A few movies later on Benji the Hunted, a camera assistant with a bias toward capitalism discovered a prescription for part of the pain and made a few extra dollars in the process. He purchased a dozen or so pairs of hard plastic knee pads, the kind designed to protect the limbs of professional skaters, and sold them out immediately to crew members at a good profit. Locals were probably wondering why in the world the roller derby had invaded the woods of Oregon.

“Pull the light up just a bit, Tony, right over the lens. Get closer to the camera, Frank.” Don Ready was the speaker.

“Get a smaller camera,” groused Frank.

“Get a smaller trainer,” Don grinned.

Frank tried to squeeze closer to the camera and bring Benji’s look even closer to the lens. Our floppy‑eared star was peering through the branches of a large potted plant, supposedly watching the goings‑on in the room across the hall where family, friends and police would be fretting about a kidnapping.

“It’s not too late to put on a longer lens and back up a bit,” Jim suggested. “That would appear to bring his look closer and, more importantly, it would get Tony off my back.” Tony was now straddling Jim like a horse, leaning across the front of the camera with the eye light. We must’ve looked like one of those modern sculptures, all arms and legs and no bodies.

“You know the rule,” I grumbled.

The rule was no long lenses on close‑ups.

Anyone who has ever played around with photography has no doubt witnessed the compressing effect of a telephoto lens. We learned early in the production that long lenses on Benji’s face flattened his features, made them less dimensional, and eliminated the feeling of intimacy that could be achieved with a wider lens, up close, right in the bushes with him. If the lens is right there, the perspective is different. You can feel it. It puts you virtually inside Benji’s head, examining and experiencing his every thought or reaction. If the shot is made with a longer lens from across the room, even though it’s still a close‑up, you are no longer right there with him, but now off, away, just an observer rather than a participant. The understanding of this phenomenon, I felt, was extremely important to the emotional magic of involving the audience totally with Benji and his dilemma.

Don Reddy understood, but the crew never really signed off on my relentless refusal to back the camera away. But keeping the camera so close to Benji often slowed the pace to a standstill and caused problems that dominoed in complexity. When you get that many people piled that close to a subject as small as Benji, it becomes virtually impossible to light the scene. With the camera across the room wearing a telephoto lens, there’s no one in the way, blocking lights. When it’s two feet from the subject, everybody’s blocking the lights.

“Scrunch up, Frank,” I said. “Right next to the lens.”

Frank rolled a little and tried to hold his hand right next to the lens. “Look here, Higgins,” he said.

“He looks confused,” Don whispered.

“Damn right he looks confused,” Frank blurted. “He’s wondering what the hell I’m doing down here on the floor buried under all these people!”

“Perfect,” I said. “Confusion is perfect for this scene.” I tapped Donnie on the shoulder. “Roll.”

For most of us, it was never dull, and rarely standing. Point-of-view shots became fond breathers because a camera looking at what Benji was supposed to be seeing meant that Benji wasn’t in the scene, and Frank wasn’t on the floor, and the eye-light was back in the truck. The few of us remaining around the lens could breathe a little easier. There was no fear of anyone getting squashed by Frank. And it was quieter. Frank has a catalytic effect upon noise levels, and he and I together seem to reach a critical mass.

The truly cherished commodity on the set, however, was the human actor, because an actor in the vicinity usually meant the crew would soon be standing up. Spirits would lift, knees would flex, and jokes would begin to flow.

Thin, delicate eyebrows arched skeptically over rolling eyes and the lady smiled sweetly. “I can’t print that, Mr. Camp. Tell me about the story, and the actors.”

She was giving me a clue, handwriting on the wall—or in this case the Dallas Morning News—but I wasn’t listening. I was too astonished. I had just spent thirty minutes ranting giddily about the unique concept of a dog acting, about the incredible facial expressions Higgins was giving us, about those big brown eyes and the reams of dialog they were speaking, about the dog himself and how for the first time I had come to realize that the story we were telling wasn’t purely the emotional petition I had once thought but, in reality, quite plausible. Dogs, I had discovered, can think rationally. And this particular one was extraordinary.

Not that others aren’t. But most dogs who have the intelligence, attitude and temperament to do what Higgins was doing, never have the opportunity to learn and to gain the vocabulary that Higgins—and later Benji’s—have had.

“Vocabulary?! That’s ridiculous!”

I bit my tongue because we were on the air. This was later, a radio talk show in Norfolk, Virginia, with a host that went on to imply that I was as full of dark brown bull droppings as any Hollywood hype artist.

But Norfolk radio notwithstanding, Benji has a vocabulary. He thinks, and he understands concepts. Like the concept of other. If you ask for a foot, then ask for the other foot, he switches. If he walks off and Frank tells him to go the other way, he looks back to see which other way, then takes Frank’s point and heads in that direction. He understands the concept of words like slow, hurry, easy, and not, no matter how the words are applied. When asked to perform a difficult task, you can actually witness the process as he studies the situation to determine the best approach. But none of this is particularly unusual. Sheep dogs in Europe tend entire flocks by themselves for months, keeping the sheep together, deciding when to move them from one pasture to another, even stopping the whole group to check for vehicles before crossing a road.

At a press conference in a Miami hotel suite, a dozen reporters watched Benji perform one of his standard show routines, completely unaware—until they were told later—that he had made a mess of it and would’ve never finished had he not been able to think it through.

He was wedged between two banister poles, pulling a coffee mug tied to a string of leashes up to the mezzanine level which overlooked the group below. A person, of course, would use two hands, one over the other, but Benji uses his mouth and a foot. He reaches down and pulls up a length, holds it tightly against the floor with his foot, then reaches down again and pulls up another length, holds it with his foot, and so on, until he has retrieved whatever is tied to the other end. As he performed, the leash slipped over the corner of the mezzanine floor and, because he was so snugly wedged between the banister poles, he could no longer reach it with the foot he had always used to hold it. I marveled as I watched the wheels turn. He pondered the situation for only a few seconds before he, quite logically, placed the other foot on the rope—the foot he had never before used to hold it—and went on with the routine as if nothing had happened.

Benji even understands what he’s doing when he’s acting.

“Now you’ve heard it all folks. The dog understands he’s acting! I suppose he gets script approval!”

Chicago. Another talk show host.

One of the more important sequences in the picture involved Benji moping forlornly, aimlessly through town. He knew the children were in danger but was unable to communicate what he knew to the family, who had, in fact, scolded him for trying. This is the same sequence I had visualized months earlier sitting in the bar of the Hollywood Holiday Inn with those first Polaroid photographs. For the sequence to work, indeed for the entire story to work, these scenes had to generate unencumbered empathy and support for Benji’s plight. He had to look as if he had lost his last friend. His desperation had to reach out from those big brown eyes and squeeze passionately upon the hearts of the audience.

It worked so well, that during the first rehearsal, I almost aborted the sequence. I was forty feet above the scene with Donnie and the camera in the bucket of a cherry picker—the kind utility companies use to fix power lines—and Frank was in the alley below screaming at Higgins, “Shame on you!! Put your head down!! Shame, shame on you!!”

Higgins looked as if he had, in fact, lost his last friend. It was perfect. I believed him. But I couldn’t bear to see him hurt so from the scolding.

I asked Tony to lower me back to the ground and I walked into the scene and asked Frank to hold for a minute while we talked.

“What’s the matter?” he asked, eyes wide and curious. “Isn’t this the look you want?”

“It’s perfect,” I said. “But I don’t feel right about getting it this way.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“I don’t feel right about you scolding Higgins like that.”

Frank’s eyes rolled heavenward. “Turn around,” he said. “Does that look like a scolded dog?”

Higgins was aimlessly scratching his ear. He looked up at me and yawned idly.

“Watch closely,” said Frank. He motioned Higgins onto his feet and began scolding him again. Our floppy‑eared star’s head dropped like a rock, his eyes drooped and he looked as pitiful as anything I had ever seen. Then Frank relaxed, chirped a simple “Okay,” and as if he had flipped an emotional switch, Higgins blinked away the blues, had a good shake, wagged his tail, and awaited his master’s next command. He fully understood what was going on, and scolding wasn’t it. He might not have known the word, but he was, in the truest sense, acting.

He picked things up so quickly that he even astonished Frank on occasion. Like the time we realized he had deciphered what cut and print meant. Frank unraveled from beneath a pile of people and suddenly realized his dog was nowhere in sight. “Your dog’s no fool,” Tony chuckled. “Joe said ‘cut’ and he split for the air conditioning.”

Attached to our portable air conditioner was a fifty‑foot hose, fifteen inches in diameter, and attached to the end of that was a little cubicle enclosed on the top and bottom and two sides. This was Benji’s home between shots. The air was necessary to keep him from panting.

Benji learned very quickly that the air conditioner was his and that’s where he was supposed to be when the camera wasn’t rolling. It didn’t take him long to figure out that the camera quit rolling whenever I said “Cut.” So off he’d go, without a word from Frank. Whenever I said “Print,” the shot was probably over, another one checked off the list, and Higgins would prance happily over to Frank’s wife, Juanita, and gather up a few “Good boys.”

But telling these stories, and a dozen others, left not the slightest dent in the structured armor of the Dallas Morning News reporter covering the newly emerging film production scene in north Texas. Movies, after all, are actors—real actors—and scripts, and cameras, and glitz. And that’s what this reporter was going to write about in the newspaper. The story came out the next day, to our amazement, on the front page! It was all about a seven-year-old Dallas girl and a nine‑year‑old Dallas boy making their motion picture debuts. The dog was barely mentioned.

That was my first experience with newspaper writers and I should’ve paid more attention. It might’ve saved weeks of frustration a year later. I had thought, naively, that the uniqueness of Benji would speak for itself and the dog’s ability to express emotion would propel him immediately into the hearts of audiences. He was the emotional focal point of the story, the three‑dimensional character playing off the humans as virtual props. With real audiences, that’s the way it worked. But not with the press. Early critics killed us. A trite and clichéd story, they said. The acting wasn’t memorable. Neither was the directing. And nobody talked about the dog!

I was destroyed. How could I have been so wrong?! They were missing the point and perspective of the movie. The soul of our scruffy little dog seemed to be buried under the critical process, the charge to analyze, while critics searched feverishly—and in vain—for the souls of the people. “The people are incredibly one-dimensional,” said one. That’s what they’re supposed to be! I wanted to screech. The dog has the depth! The story is not the people, and not the kidnapping! It’s the dog’s struggle to communicate something to a group of humans with whom he has no way to converse! But that’s not the way they saw it. Their critical check list had been structured over the years, based upon all the movies that had gone before, all of which were anchored in the emotions and relationships of people, not dogs. Even in movies about animals, the concern, the compassion, was not with the animal, but with the kid who had to dispose of the animal because the animal was killing the chickens.

It took a full week to pull myself off the floor after the first bad reviews came in, and still another to push ego aside, analyze the problem, and figure out how to solve it. God was saying now is the time to fix this, not later.

But now I’m getting ahead of myself.

Theme from Love Story was playing on the car radio. I was intrigued by the way these classical strains tugged at my emotions and left me sort of sad and empty. I turned to see if Carolyn was listening, but didn’t need to ask. The tears spoke the answer. She hadn’t read the book and knew little about the film, but was responding to the music as if she were living it.

I told that story to Euel Box the first time we met. “That’s the kind of music we must have for Benji,” I said.

And with filming and editing on the picture complete, I was now telling him, quite seriously, that our movie was still only half done. The rest was up to him.

Like most of us on the picture, Euel lived in Dallas and had never worked on a theatrical feature before Benji. He had composed music for dozens of television commercials and hundreds of those radio station jingles that sing out call letters like they were classic lyrics to a hit record. But it was his enchanting theme for a jewelry commercial that had caught my ear several years before. The spot featured a young couple in love, walking in a park awash with springtime azaleas. Soft, romantic photography circled and swirled about them, eventually settling upon a close-up of the inevitable engagement ring, and a priceless, stunning reaction from the beautiful young girl.

This commercial could’ve easily fallen into the ranks of the dumb and clichéd, but the execution was perfect. The direction and photography were lusciously understated, and Euel’s music was exquisite. I wanted to grab Carolyn, race out to the park and propose all over again. It was emotional magic.

Even then, long before Benji, I knew I didn’t want to forget this composer’s name, and that early decision resulted in one of the happy surprises of the Benji production.

But it wasn’t easy, and it didn’t come quickly. Still another testimonial for perseverance. First, I had to literally shake Euel out of a kiddie music gridlock. He knew that children would be in the audience and he was writing down to them, Mister Rogers‑like.

After listening to the third or fourth piano demo, I took a deep breath and paced across the room.

“I’ve asked you to think of Benji as an adult movie that will also entertain kids,” I said, “not the reverse. I’ve asked you to move me with your music and promised that by doing so, you’ll also move my kid! I’ve asked you to look at the Disney classics! Listen to Love Story! Go back and listen to your own jewelry commercial music! But it’s simply not working. Either you haven’t heard a thing I’ve been saying… or perhaps I’ve made a terrible mistake.”

Something clicked. No more Mr. Rogers.

But no Academy Award nominations either. And that, quite literally, was the next stumbling block. When Euel and I first talked about the movie, I had told him that the opening song was going to have to win an Academy Award nomination. He didn’t think I was serious, of course, and when he finally realized that I was, he decided, most certainly, that I was crazy. I had done a study of movie songs that had been nominated for the Award, and, at the time, it was sort of a throw-away category. It seemed to me that this was an area in which we might have a realistic shot at a nomination; which, if achieved, would certainly bestow credibility onto our unknown movie about the unknown dog by the unknown company with the unknown director. I had no idea, until later, how much pressure this put on Euel and his writing efforts, compounded when I asked him to create a melody that would work both for the bright and cheerful (Academy Award quality) opening song and the slower, more poignant underscoring later in the film. I felt that subconscious familiarity with the melody line—from the opening piece—would strengthen the emotional impact of the slower, more plaintive pieces later in the film.

But trying to make a single melody accomplish two separate objectives, both very important, and both very different, caused more creative clog. Finally I told Euel to forget the romantic and poignant stuff for the time being and concentrate only on the opening song. It’s funny how the mind works. Remove the barriers, tell that globular, gray, gelatinous mass it no longer has to make one piece of music do two jobs, and what comes out is a beautifully haunting melody that works splendidly both ways.

I’ll never forget the night I heard the final recording. I had been in looping sessions all day while Euel, his wife Betty, and a large orchestra were recording music. I met Betty a block from the studio and as we walked I asked how the session had gone.

“Pretty good, I think,” she said nervously, which is not exactly what I wanted to hear. We entered the control room where Euel and two engineers were mixing the day’s sessions and, for a moment, everything seemed to freeze and get very quiet. Euel sat me down in a chair right between four huge speakers, asked Jerry Barnes, the chief engineer, if he was ready, apologized to me because I would be hearing a rough mix, not a final; then the tape rolled. I was listening to two of the three most important pieces of music in the film. Each had to reach deeply, sensitively into the emotion and squeeze softly with all its might. This kind of music you shouldn’t even be aware of hearing, only feeling.

I didn’t last long. Three, maybe four minutes and I had to leave the room. I scampered down the darkened halls of the deserted studio, turned a corner by a water fountain, and there I stood for a very long time, yes, with tears streaming down my face. I had never in my life wanted anything to be so good, and had it turn out even better than I could’ve hoped.

It must’ve been at least ten minutes before I could pull myself together and return to the control room. Euel and Betty and the engineers were all seated, just staring into space, sort of glassy‑eyed, looks of devastation sagging on their faces. They were certain I had hated the music. Why else would I have simply gotten up and left like that?

I circled the room slowly, trying to portray the producer, the guy who was supposed to be in control, but the little boy crying happy tears in that theater back in Little Rock kept getting in the way. Words were difficult to squeeze out. “Until tonight, we had nothing but a bunch of film strung together,” I stammered. “Now, at long, long last, we’ve got a movie!”

The smoke from a huge, black cigar lay heavy across the room, stirred only by the cigar itself as it leaped from mouth to hand, swirled and circled up from the chair, danced across the huge office, then paused to jab at the air like a driving piston.

Ed and I sat in stunned silence. There was a dank, black empty feeling oozing down over me. Cold and distant, yet agonizingly painful. The words spewing from the smoke of the fat man’s cigar, were going astray, some hitting, some missing. I was drifting in and out. Had all of this been for nothing? The question was directed at God. With attitude I’m afraid. The years of preparation? The experience? The planning? The dreams?

“Totally wrong for Paramount!” barked the mouth behind the cigar. “It’s too damn sweet. And the music is… well… it’s… it’s too sticky… it’s all wrong. If you cut the Clairol sequence, we might try something with Saturday matinees, but beyond that… I mean, at night it doesn’t have a chance! Have you tried Disney?”

The words fell out of his mouth like crystal shattering on a tile floor. We had tried Disney. And Fox, and MGM, and Warner Brothers! And this simply couldn’t be happening!

It’s a good movie, I tried to reassure myself. It works. Reaction to the first screening had been terrific. The audience was mostly investors, friends and crew, but you could still tell, like the difference between a serious hug and a pat on the head. And at the exhibitor’s convention in Dallas, theater owners had loved it, or so they had said.

Years of hopes and dreams, eons of study, practice and hard work had finally come together in a movie. A real movie that real audiences would cherish. I was certain of it. I had seen it in their eyes during the screenings. They laughed and cried, and burst from the theater with big smiles stretched across their faces. It was all working. Except for one thing. We couldn’t get a distributor. No one wanted it. Not one. Zero.

—–

As mentioned earlier, the above is an excerpt from God Only Knows – Can You Trust Him with the Secret. If this piqued your interest I hope you’ll fill in the gaps before and after by reading the entire story. It’s inspirational, and I hope will give you an insight into why you should keep driving forward even when things seem their darkest. Cherish those adversities. When we came back from Hollywood without a distribution deal we had to either throw the film in the trash, or figure it out. So we raised still more money and started our own distribution company. One year later Weekly Variety reported that Benji was the #3 picture of the year.

Here’s what Kathleen says about it: Hi everybody. This is Kathleen. I sent Joe to the barn so I could write this piece of truth… about this book. This one’s more about Benji and less about horses… unless you’ve ever wondered what kind of person could begin writing a book like The Soul of a Horse less than a year-and-a-half after acquiring his very first one. This book will answer that question (in spades!). Because this journey is the one that created the man who has meant so much to you and your horses. You will love it. I promise. Thanks bunches and thank you so much for the support and encouragement you’ve given my hubby – Kathleen

Joe

In February, 2018

a glorious HD Widescreen digital restoration

of the original Benji

was released

on Blu-ray, DVD and streaming.

READ MORE